Reasoning over Alpha Existential Graphs Link to heading

In the previous post, we have seen how to represent propositional logic statements as existential graphs (EGs) and vice versa, but merely representing logical statements in an alternative format isn’t all that interesting on its own. In order for existential graphs to be useful, they should provide us some means of reasoning over logical statements, allowing us to derive meaningful conclusions from hypothesis and prove logical equivalences.

In order to perform reasoning within a logical system we need a set of inference rules that specify how we may legally take one formulae (in our case an Existential Graph) and derive another from it. These inference rules should be sound with respect to the semantics of the logical system and hence not allow us to derive any false statements. A further discussion of inferences can be found in [2], we will be using the inference rules presented by [1] and taking for granted their soundness which has been proved in [3].

Inference Rules Link to heading

With these definitions out of the way we can now enumerate the rules of inference of existential graphs. For our examples we will use the EG applet developed by Bram Van Heuveln, one difference between this and the format we have seen so far is that cuts in this application are drawn as squares rather than ovals.

Double Cut Introduction and Elimination Link to heading

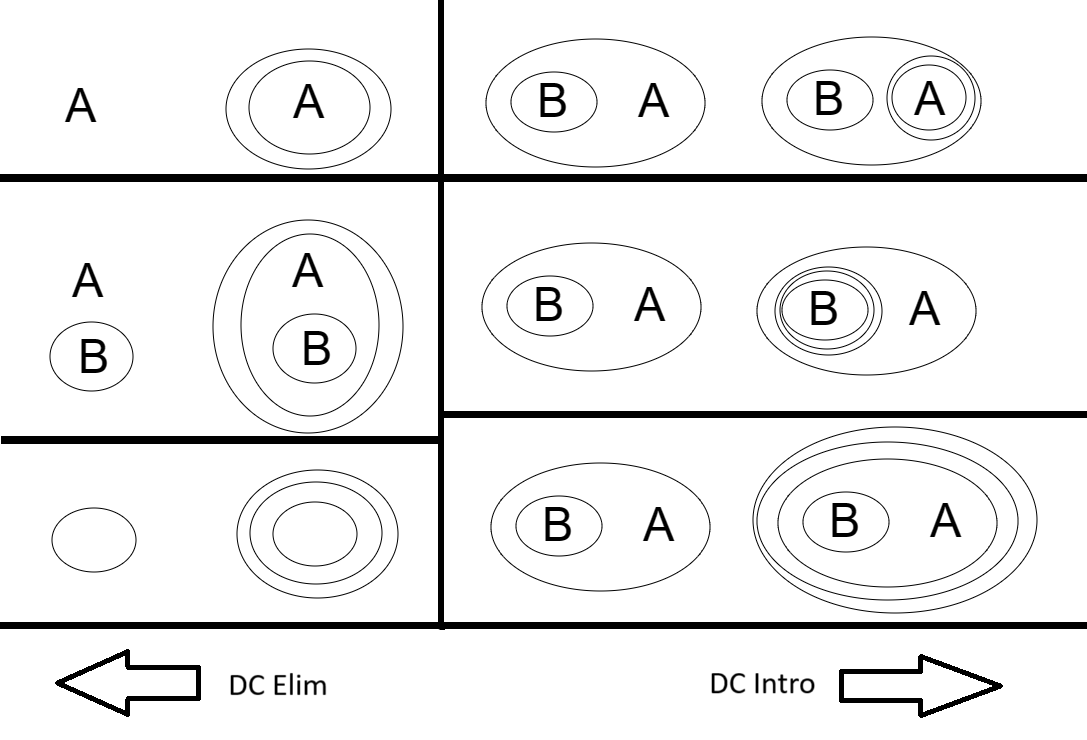

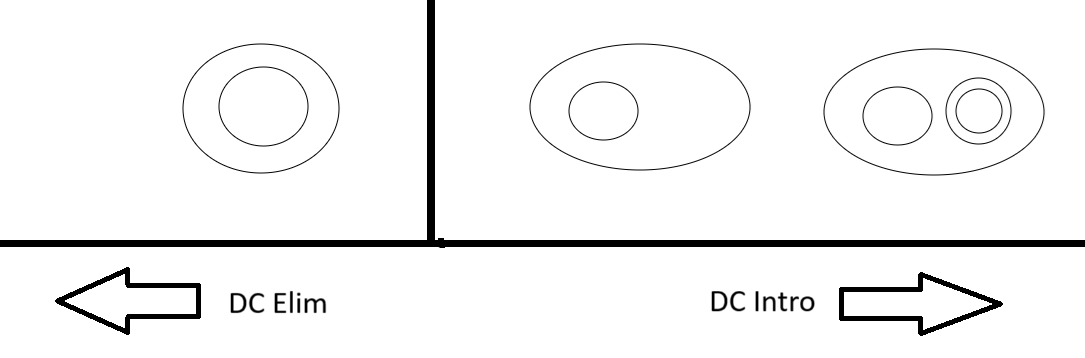

Double Cut Introduction states we can introduce a double cut around any subgraph and the resulting EG will be logically equivalent to the original EG. Double Cut Elimination says we can do the same thing in reverse, remove a double cut around any subgraph and it will be equivalent. This rule corresponds with the fact that double negation cancels out everywhere. We can prepend or remove $\lnot\lnot$ to any formula or formulae in propositional logic and it will not change its meaning (truth-value).

In these examples, we can move from the left graph to the right graph by applying double cut introduction. To get back to the original we may apply double cut elimination. The three examples on the right showcase that there are many different ways we can introduce a double cut to the same graph, since we can move back using double cut elimination, we can derive any of these EGs on the right from another purely using double cut introduction and elimination. Note that in the middle right example, its not entirely clear if we introduced the double cut around the $B$ or the $(B)$, but it doesn’t matter, we could have done either.

Note importantly that double cut elimination only works if there is nothing on the same level of the inner cut, we cant’t use double cut elimination to derive $A,B$ from $(A (B))$ since $A$ appears on the same level as the inner cut that surrounds $B$.

One important thing to note is that since $\empty$ is a subgraph of everything, we can use double cut introduction to place an empty double cut anywhere, much the same, we can use double cut elimination to wipe any empty double cut out of existence on any level.

Insertion Link to heading

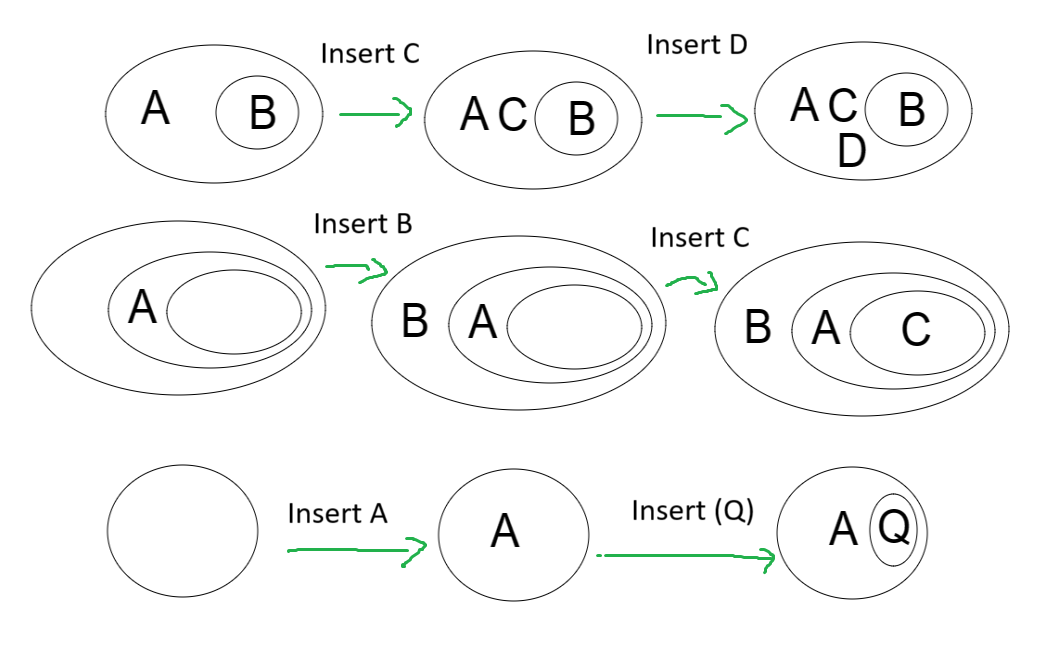

The Insertion rule states that you can insert ANY graph as a subgraph at any odd level in an EG. This rule is quite powerful, as you can insert quite literally any graph you can dream up on an old level.

What is really going on here? Formally this rule corresponds to the rule in propositional logic known as “Strengthening the Antecedent”[3] represented in propositional logic by the tautology: $$(A \rightarrow B) \rightarrow ((A \land C) \rightarrow B)$$ This says that if we know $A$ implies $B$ then we know that $A \land C$ also implies $B$. This is clearly because due to $A$ implies $B$, we know $A$ alone is sufficient for $B$, thus regardless of what else is added to the antecedent, we can be sure $B$ will follow.

We can directly see this correspondence between the Insertion rule and strengthening the antecedent in our first example where we start with $(A \rightarrow B)$ apply Insertion to get $((A \land C) \rightarrow B)$ and again to get $((A \land C \land D) \rightarrow B)$. What about the other examples? On the bottom we start with an empty cut. Classically this empty cut AGE represents Falsehood $\bot$, but how else can we interpret it? Lets remember that all AEGs have the empty subgraph $\empty$ as a member, and $\empty$ represents Truth $\top$ (hence why the empty cut $\lnot \top$ is said to be $\bot$). We can also represent truth as the empty double cut $\lnot \lnot \top$. Thus we can say we have two instances of the empty subgraph inside our cut, one $\top$ and the other $\lnot \lnot \top$. In other words, the empty cut $()$ is equivalent to $(\empty ((\empty)))$, logically $\lnot(\top \land \lnot \lnot \top)$ or better yet read as an implication $\top \rightarrow \bot$, now applying strengthening antecedent we can add $A$ like so, $(\top \land A) \rightarrow \bot$ which simplifies to the single cut containing $A$ follows by expanding the $\rightarrow$, canceling double negation, and eliminating redundant $\top$s: $$ (\top \land A) \rightarrow \bot$$ $$ \lnot ((\top \land A) \land \lnot \lnot \top)$$ $$ \lnot (\top \land A \land \top)$$ $$ \lnot A $$ We can use the same process to prove that we can introduce any arbitrary subgraph on ANY odd level. As an exercise, the reader should look at how this plays out for the middle example, in which we insert $C$ at level 3.

Note that just as strengthening the antecedent is not reversible ($ ((A \land C) \rightarrow B)\rightarrow (A \rightarrow B)$ is not a tautology), neither is the insertion rule for AEGs, once you insert something, there is no rule to get you back.

Erasure Link to heading

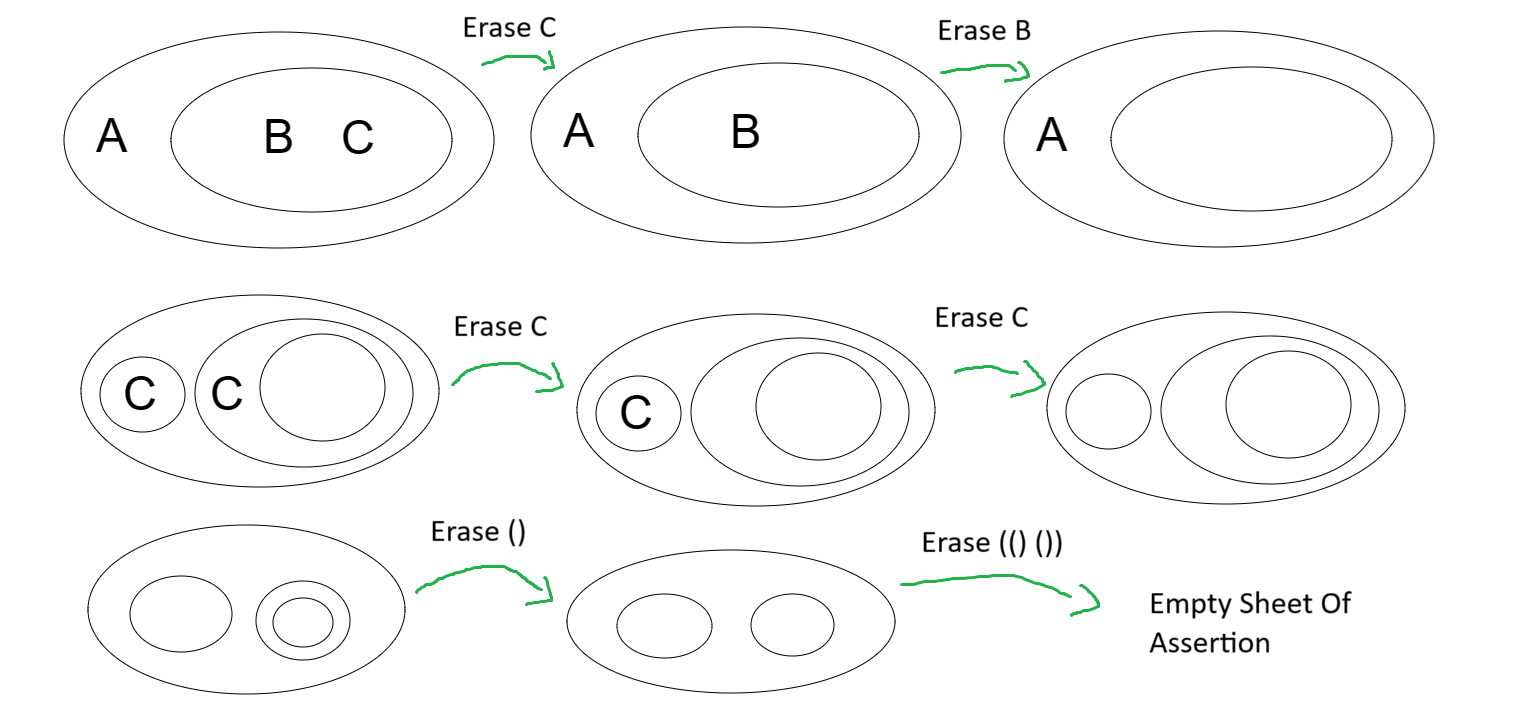

The Erasure rule states that you can erase any subgraph at an even level.

Formally this rule corresponds to the rule in propositional logic known as “Weakening the Consequent”[3] traditionally written as: $$(A \rightarrow B) \rightarrow (A \rightarrow (B \lor C))$$ But for our purposes we will better be served by the equivalent: $$(A \rightarrow (B \land C)) \rightarrow (A \rightarrow B)$$ The correspondence is clear from the first example, in which we have $A \rightarrow (B \land C)$ and using erasure derive $A \rightarrow B$. We can then apply this further by seeing that $A \rightarrow B$ is equivalent to $A \rightarrow (B \land \top)$ and weaken the consequent removing be $B$, leaving us with $A \rightarrow \top$.

But why does this allow us to erase anything from the sheet of assertion at level 0? We will show this ability follows from double cut insertion/elimination, and weakening the consequent. Much like in the last example the sheet of assertion contains as many empty subgraphs $\empty$ as we want. Lets assume some arbitrary subgraph $\phi$ we want to erase is on the sheet of assertion. We have $\phi \land \top$. Now we apply double cut insertion to get $((\phi \ \empty))$ written in propositional logic as $\lnot \lnot(\phi \land \top)$. Since $\top$ is on every level we can write this as if its on level 1 by adding it like so $(\empty \ (\phi \ \empty))$, which when written in propositional logic reads: $\top \rightarrow (\phi \land \top)$ apply weakening the consequent to obtain $\top \rightarrow \top$ which is just $(\empty \ (\empty))$, the empty double cut $(())$ which can be removed from the sheet of assertion with double cut elimination. A similar process generalizes to even levels.

References Link to heading

[1] Van Heuveln, B. (2023, March 29). Existential Graphs [public talk]. New York Capital Region Logic Reading Group, NY, USA. Retrieved July 28, 2023, from

https://homepages.hass.rpi.edu/heuveb/Teaching/Logic/CompLogic/Web/Presentations/EG.pdf.

[2] Roberts, D. D. (1973). The Existential Graphs of Charles S. Peirce. (T. A. Sebeok, Ed.) (Vol. 27, Ser. Approaches to Semiotics). Mouton.

[3] Van Heuveln, B. (2002, June 6). Formalizing Alpha: Soundness and Completeness [web slides]. Retrieved July 31, 2023, from

https://homepages.hass.rpi.edu/heuveb/Research/EG/details.html.