On Performance Link to heading

While not mentioned much on my blog, back in the day (circa 2018) I considered myself something of a programming languages junkie and C/C++ evangelist, who’s job was to purge the internet of unholy Python users. While I’ve since mellowed out, and have myself become a regular Python user, I think at least some of my crusade for C/C++ was well motivated, particularly my favorite talking point: performance.

I am certainly a proponent of the cliche “choose the right language for the job”, and am also aware of the many of considerations beyond performance: development speed, error proneness, formal verifiability, ease of hiring someone to join your project, ease of codebase management, etc. However, there is something that feels very primal about performance (and freedom to manage memory to improve performance) as the ultimate measure of a language’s usefulness for developing performant top-of-the-line software. Clearly others agree, as the majority of software I use day-to-day is written in C/C++, presumably for performance (or written in a performance focused language meant to replace C/C++). Anyone who disagrees is welcome to write a theorem prover in the language of their choice and try to beat Vampire or E at CASC.

In terms of popular imperative programming languages, the past decade has shown a clear direction as well. Most people I know seem to agree that C/C++ is great in terms of performance and we would like to keep this as a feature of new langues going forward. They can also agree that C/C++ has a lot of issues, but no one can seem to agree on what C/C++ actually got wrong, everyone has their own list. The result is many new and relatively performant languages inspired by C/C++. Go and Rust are the first ones that should come to mind, but there are also a host of other less popular and indev languages that aim to fix their own gripes with C/C++, such as Carbon(out of Google), Cppfront(from C++ legend Herb Sutter at Microsoft), Jai(by indie game developer Jonathan Blow), and many more…

While I’d love to now turn this into a post about how we cant just create 10+ replacements for C/C++ and expect things to end well, this post is actually about Jai. Jai is based on Johnathan Blow’s list of complains about C++, written up during his time as a C++ game and engine developer. While Blow primarily intends Jai to be a language for developing games, he’s made no secret that he thinks it may be more broadly applicable outside of this niche.

On Jai and Joy Link to heading

Two things Jai focuses on that stood out to me when first hearing about it are compile speed and “joy”. Jai aims to maximize joy all while staying as performant as C/C++. While a discussion of compile speed and Jai’s philosophy about compilation deserves its own post, I will briefly mention that Jai blows current C/C++ build speeds out of the water and will likely keep going (See this post for a rough analysis of C/C++ lines/sec on popular compilers; Jai’s goal before release is 1 million lines/sec). I personally have to build large C/C++ applications from scratch on a regular basis, so I am a fan.

I was skeptical at first about claims that Jai brings “joy”, as I’ve heard many languages claim to bring joy to developers (most recently Clojure, which is not brining me much joy). I was however pleasantly surprised by my first experience with Jai, it did indeed bring me joy. Rather than tell, I will show, we will run through my simple Jai program in the second half of this post, and you can judge for yourself if its joy-worthy.

Rage Against Boilerplate Hell, Can Jai Help? Link to heading

Over the years I’ve made few forays into graphics programming and game engine development:

- In 2017, I wrote a 3D OpenGL based game engine in Java as my final project for my AP Java class.

- In 2018, I write a two separate 2D HTML5 canvas based engine in Javascript, one for a sidescroller and another for a top down RPG.

- In 2020, I created a bare bones 3D Vulkan engine in C++ and got it to render some entities.

My final experience with Vulkan was enough that I swore I would never write another engine again and if I ever needed to do something in 3D again, I would use an existing engine such as Godot, Unity, or Unreal (This would later come back to bite me, and is still biting me). My biggest complaint about Vulkan is the amount of boilerplate. While Vulkan is supposed to be a low level API, most people I talk to who have only used OpenGL (and believe OpenGL is a low level API), do not fully comprehend the amount of boilerplate needed to get off the ground in Vulkan, easily over 1000 lines of functions you’re just seeing for the first time, plus the need to install a bunch of validation layers and an SDK to actually develop with it.

Jai was developed with game development in mind, and one of the first things I heard about it is that the standard library comes equipped with a module, Simp for basic graphics programming. Let’s write a program to draw a quad with a texture to the screen… and see if it brings joy.

Lets render an image to the screen! Link to heading

We’ll start by importing the module’s we’ll be using.

Win :: #import "Window_Creation";

Basic :: #import "Basic";

Simp :: #import "Simp";

Input :: #import "Input";

Lets discuss what these modules do. Window_Creation provides a simple crossplatform module for Window creation. If this were C or C++ we would be calling glfw right now, but Jai has us covered right in the standard library. Basic is our stdlib equivalent, and contains common functions such as print, assert, array copying, etc. Simp is our bread and butter, it is a basic crossplatform graphics API right in the standard library that requires minimal setup, it provides functions for loading images and rendering to the screen. Input provides crossplatform input handling and provides methods for detecting key presses, window events, etc.

Now onto code, lets define a basic function that loads a bitmap from a file using Simp’s bitmap functionality.

get_bitmap :: (filename : string) -> Simp.Bitmap{

bitmap : Simp.Bitmap;

good := Simp.bitmap_load(*bitmap, filename);

Basic.assert(good, "Failed to load bitmap from %", filename);

return bitmap;

};

* as the “address of” operator, which is unary & in C/C++.Now lets write our main function as our entry point. We’ll structure main as follows, First we’ll set up a window, second we’ll load a texture to render to the window, and finally we’ll have an event/render loop that polls the window for events and renders the texture.

main :: () {

First we’ll create a window with the Window_Creation module and give it to Simp for rendering.

w : s32 = 400;

h : s32 = 400;

win := Win.create_window(w, h, "Window Title");

Simp.prepare_window(win, 8);

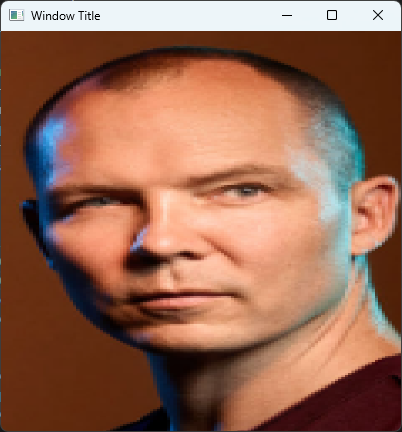

Next we’ll prepare our texture for rendering using the function we defined above. I’m using a nice pixelated png of Johnathan Blow (blow.png) as our texture we’ll be rendering.

bitmap := get_bitmap("blow.png");

image : Simp.Texture;

Simp.texture_load_from_bitmap(*image, *bitmap);

Now the main render and event loop, we’ll assign a name to the condition to check out a cool feature of Jai, breaking out of arbitrarily nested loops.

while no_quit := true {

First things first, lets poll the window for events using the Input module and break the loop if the user

closes the window.

Input.update_window_events();

for Input.events_this_frame {

if it.type == .QUIT

// Testing out Jai's cool ability to break

// out of multiple nested loops

break no_quit;

}

Finally we can use Simp’s built in functionality to render the image to the screen.

Simp.clear_render_target(.15, .08, .08, 1);

Simp.set_shader_for_images(*image);

Simp.immediate_begin();

fw := cast(float) w;

fh := cast(float) h;

Simp.immediate_quad(.{fh, 0}, .{0, 0}, .{0, fw}, .{fw, fh});

Simp.immediate_flush();

Simp.swap_buffers(win);

Basic.reset_temporary_storage();

}

}

Alright and now we can compile it:

jai main1.jai

and run it:

main1.exe

and voilà

Coming from Vulkan or even OpenGL where this would have been either 1000+ lines or 300+ lines respectively, we’ve accomplished this in a cross platform way in just 50, using only things provided by Jai’s standard library. This does indeed bring me joy.

All code in this post is available here on my GitHub.