A Logicist Mage’s Manifesto Link to heading

Dungeons and Dragons and the consequences of its magic system has been a disaster for the human race. The notions of (1) tiered magic, and (2) distinct well-thought-out spells that can be learned via training, leveling, or purchase with skill points, has permeated the fantasy world magic systems of innumerable video games, books, and other media. The ideas put forward by these systems can be summed up in one word: dumb. These systems dumb magic down from the very aesthetic many of these same worlds ascribe to it: an intellectual pursuit. In the majority of magical settings, mages are portrayed as scholars, academics, researchers, and intellectuals; yet rarely do the magical systems in these worlds mirror the intellectual dignity or rigor one would expect of them given their scholarly aesthetics. In this work, we outline a logicist framework for constructing and worldbuilding magic systems in which spells are meaningful (rigorously defined), and aesthetic.

The World as a Set of Facts Link to heading

The world is the totality of facts, not of things. For the totality of facts determines both what is the case, and also all that is not the case. The facts in logical space are the world.

–Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, Ludwig Wittgenstein, 1921

The logicist views the word as a collection of facts. The magician manipulates the world through magic. On these premises, magic manipulates the facts that define the world. A spell to the logicist mage then is a statement about some facts in the world that should be made true, and the act of casting the spell is the process of these facts being made true by extra-natural means.

For example lets turn to a classic ignite spell. As a mage we may wish to light some monster on fire. A fact of the world is that the monster is not on fire, our spell is the statement “The monster is on fire”, casting the spell changes the state of the world such that the monster is now on fire.

Of course, not all spells are created equal. Assume no monsters in the world are on fire, then the spell that lights 100 monsters on fire represented by the statement “100 monsters are on fire” is more powerful than the spell represented by the statement “A monster is on fire”. The first spell is more difficult to cast because it is more out of line with the current facts of the world, and thus more extra-natural means are required such that the world comes to a state in which 100 things are on fire. The extra-natural energy expended to change these facts is left up to the world builder, it could be mana, divine power, or any other extra-natural currency, that fits within the world’s setting.

Spells as Statements Link to heading

The “Spells as statements of truth” paradigm aligns well with the notion of speaking the world into existence found in Abrahamic religions. God in a logicist mage’s world can be seen as omnipotent being making statements of truth with no regard to how far these statements deviate from the current state of the world as god possesses infinite extra-natural energy to bring things about.

A world builder looking to create a serious magic system within a logicist magic paradigm must then contend with deciding the most important parts of the magic/logic system: a syntax and semantics for spells as statements about the world. Thankfully, logicians have been working on this very problem, representing facts about the world in a formalized way, for hundreds of years.

Atomic Spells, Compound Spells Link to heading

The foundational unit of truth in the logicist mage’s system is the atomic predicate. Atomic predicates are the smallest level of truth about objects in the world. For example in our ignite spell, “x is on fire” the an atomic predicate, it describes a fact about some object x in the world, we may plug in any object in the world as x and have a statement/spell. In predicate logic we write the spell “Monster is on fire” in a way such that it is clear what are objects and what are predicates, with objects inside parenthesis. $$ OnFire(Monster) $$

Predicates may also take multiple objects and relate them. For example lets say entanglement is an atomic property that says two objects are entangled, think of an entangle spell that binds two objects together. Let Monster A and Monster B be objects in the world, then we can have the spell “Monster A is entangled with Monster B” makes it such that Monster A and Monster B are bound together. In predicate logic we write this as $$ Entangled(Monster A, Monster B) $$

To build more complex spells we may look to the basic logical connectives from propositional logic: Negation “not”($\lnot$), Conjunction “and”($\land$), Disjunction “or”($\lor$), and Conditionals “if … then …”($\rightarrow$). Using the atomic predicates $OnFire$ and $Entangled$ we define some more complex spells, and provide an informal meaning/semantics for each.

| English Spell | Predicate Logic Syntax Spell | Informal Semantics |

|---|---|---|

| A is not on fire | $\lnot OnFire(A)$ | Extinguishes A if it was on fire |

| A is on fire and B is on fire | $OnFire(A) \land OnFire(B)$ | Sets both A and B on fire at the same time |

| A is on fire or B is on fire | $OnFire(A) \lor OnFire(B)$ | Sets either A or B or both on fire |

| If A is on fire than B is on fire | $OnFire(A) \rightarrow OnFire(B)$ | Sets B on fire if A is already on fire. |

| A and B are entangled, or A is on fire and B is on fire | $Entangled(A,B) \lor (OnFire(A) \land OnFire(B))$ | Either entangles A and B, or sets them both on fire, or both |

| If A is on fire and B is not on fire, then A and B are entangled | $OnFire(A) \land \lnot OnFire(B) \rightarrow Entangle(A,B)$ | If A is not on fire and B is not on fire, entangles A and B |

| A is on fire and A is not on fire | $OnFire(A) \land \lnot OnFire(A)$ | A contradiction, this can never be made true in the world |

These compounds give rise to a few interesting properties that we note here: First we can negate facts about the world, hence our “is on fire” predicate can be negated to form an extinguish spell. Conjunction allows us to make multiple facts true in a single spell. Disjunction allows for some notion of random outcome as multiple outcome worlds (sets of facts) may match the spell. Conditionals allow for conditional spells that only modify the world if something else is already true. A spell that states a contradiction such as $OnFire(A) \land \lnot OnFire(A)$ is an interesting construct as it is impossible to make both $OnFire(A)$ true and false simultaneously, perhaps the spell fizzles, or explodes, this is left up to the world builder.

Existential Spells, Universal Spells Link to heading

So far we have been talking about spells that light a named individual on fire, but there is a strong case to be made for magic systems in which one can not talk or directly identify an individual by name (infact this is the authors’ preferred system inline with our magic circle system). We need a way of talking about arbitrary and non-named objects in the world and we do this via the notion of quantifiers from first order logic.

Quantifiers come in two flavors, existential quantifiers that allow us to make statements about an arbitrary objects that exist “There exists some object O such that [something about O]”, and universal quantifiers that allow us to make statements about all objects in the world of the form “For every object O, [Something about O]”. For example, the statement “A monster is on fire” is an existential statement, Using the quantifiers it would be read, “There some object O, such that that O is a monster and O is on fire”. In first order logic we write this: $$ \exists O: Monster(O) \land OnFire(O) $$ The universal spell “All monsters are on fire” would be read “For every object O, If O is a monster than O is on fire”. which we write: $$ \forall O: Monster(O) \rightarrow OnFire(O) $$

For the sake of argument, there are only a finite number of objects in the world we can talk about in our spells, and we can thus use the truth functional expansions of the quantifiers to help us better understand how these statements may be interpreted. If the world contains monsters $O_1 \cdots O_n$ then “A monster is on fire” can be read “$O_1$ is on fire or $O_2$ is on fire or $O_3$ is on fire…” thus leading the spell to make it so that the some monsters are on fire. The universal spell “All monsters are on fire” can be read as “$O_1$ is on fire and $O_2$ is on fire and $O_3$ is on fire…”.

Note that the universal spell is extraordinarily powerful, perhaps too much so, lighting all monsters in the world on fire is quite a spell, and probably requires too much extra-natural energy for any normal mage to cast. World builders should decide what happens in these situations, if the user runs out of mana, or can even cast it at all. Alteratively perhaps the or the domain is only what the caster perceives so the statement “All monsters are on fire” is closer to a “All monsters i can see are on fire” or a “All monsters near this spell are on fire”.

We again return to the important point brought up in the beginning of this, existential and universal spells allow us to cast spells on objects that we may not know the name of or have an identifier for. Lets say you’re fighting two monsters A and B one at a time. To light them on fire you need to cast two septate spells “A is on fire” and “B is on fire”, but this is inconvenient. Lets add a special atom “x in front of caster” to denote that the object x is infront of the individual casting the spell. We can now say the following without referring to the specific names of the monster, to the same effect, a general ignition spell. “Any monster infront of the caster is on fire” or “If there exists a monster infront of the caster, than it is on fire.”

Temporal Spells, Mind Control Spells, Spells about Spells Link to heading

The logics we have looked at barely scratches the surface of what is possible to represent in these systems. Modal logics allow us to make extremely robust statements about the world including:

- Temporal logics which allow us to make statements about time: when something will be true and how long it will be true for.

- Epistemic logics, which allow us to make statements about what agents know and believe.

- Metalogics which allows us to use logic to talk about logic.

It is not hard to see the consequences of these for the logicist mage’s magic system. Using temporal logics mages may express statements such as “It will always be the case that Monster M is on fire” or “Monster M will eventually not be on fire”. Using epistemic logics we may make statements about what individuals in the world believe “Monster A believes Monster B is an enemy” leading to a foundation for a form of control magic mind reading, and conjuration. Using metalogics we make make statements about spells as if they are objects, and spells may have their own meta atomic predicates “All spells can not destroy this rock” “The spell being cast by the monster infront of me will fail”.

The depth enabled by these logics is enormous but for world builders attempting to implement a logicist magic system in practice, particularly for games, should take into account the complexities of implementing these systems even for finite worlds, for the implementor it is probably a good idea to max out at first order multi-modal logic.

The Laws that govern Magic: Axiom Schemata Link to heading

What exactly do Mages research all day?!

–Anonymous Mage

So far we have used very high level atomic predicates that directly correspond to a spell, but there is no rule saying this has to be the case. Indeed perhaps you also think the act of merely stating someone is on fire and it being brought about is too simple of a magic system.

Lets say we have the atomic predicates “x is at temperature t” and “x is flammable”. Something in the world appears to be on fire if it is over 100 degrees and is flammable, but being on fire isn’t an atomic property in of itself, its just a linguistic construct made by humans in the world to describe what they see. In this case the fire spell must be phrased in terms of atomic predicates no longer as the statement “x is on fire” as this is only meaningful in the language of humans, but not the language of the world. Thus we state the spell “x is on fire” as using the more fundamental “x is at temperature 100 and x is flammable” in a world with this magic system.

So far all predicates we have looked at operate in a vacuum independent of eachother but predicates often do not operate in a vacuum, and the truth of one may influence the truth of another. Lets assume now that “x is at temperature t” and “x is flammable” and “x is on fire” are all atomic predicates in our magic system. If “x is flammable” and a mage casts the spell “x is at temperature 100” we would like it to be the case that “x is on fire” as something of a law of nature about the world. Here we can introduce axioms and axiom schemata that relate predictaes and function as the laws that govern the magical world: for examples the statement “if x is at temperature 100 and x is flammable than x is on fire” is an an axiom schemata, we can plug in any object for x to create a statement about the world that must be made true. After casting a spell, or perhaps at all times if axioms are interpreted as rules of nature, axioms should be applied to the world state as if they are a spell being cast by the world or god.

It is the job of mages to understand the axioms in their world and research them so that they may add contingency into their spells. For example a mage in the above magic who wants to heat something to a high temperature but not have it light on fire should ensure that they make it so that it is not flammable first!

It is the job of the world builder to select good atomic predicates and axioms relating them. The axioms should give rise to interesting interactions and give rise to unforeseen spells allowing, for a natural evolution of the “meta” of a magic system over time, as new discoveries are made. Selecting good atomic predicates and axioms that relate them is key to designing a good logicist magic system.

The Syntax and Aesthetics of Magic Link to heading

So far spells presented have either looked like english statements or just symbolic statements in logic. Most would agree that this isn’t very aesthetic means of representing spells. One simple way of representing these statements would be using a simple substitution cipher and using symbols for atomic statements can be effective in creating interesting looking spells.

An example of the universal monster ignition spell using the alchemical fire symbol (🜂) for the on fire predicate the brimstone symbol as the monster predicate 🜍, and omitting parenthesis, this starts to look a bit more magical.

$$ \forall \alpha: 🜂\alpha \rightarrow 🜍\alpha $$

The logic symbols themselves could also be substituted with more interesting symbols. A harder alternative is creating a new language (a conlang) such as Tolkien’s elfish languages and writing your statements in that instead, but be wary that it should be automatically parsable, but not nesisarilly uniquely parsable, as this adds more fun. Finally we turn to the most interesting way of representing logical statements, diagrams.

Existential Graphs as Magic Circles Link to heading

The magic circle is a staple of fantasy, but unfortunately in most all implementations has come to symbolize naught but aesthetic nonsense. Rarely is any thought given to the magic circle beyond its size and how many familiar magic looking alchemical symbols the artist can cram onto it. While pretty, these magic circles are the hallmark of an awful dumbed down magic system, in which creators are more concerned with aesthetics over meaning.

The question then is: Can we represent meaningful and precise statements like formulae in geometrically interesting and visually pleasing ways? One place to start is a two (or many) dimensional representation of formulae.

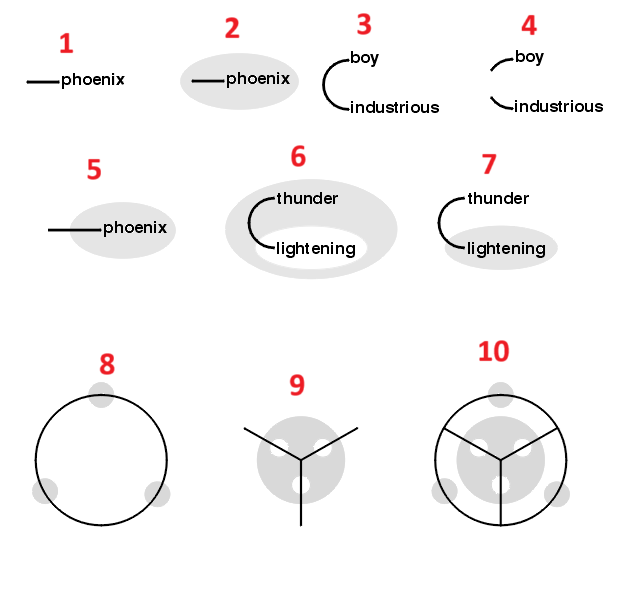

Chales Sanders Peirce worked out a diagrammatic means of representing propositional, modal, and higher order logic statements using his existential graph systems. The existential graph system corresponding to first order logic statements is known as the beta existential graph system. This is our preferred means of representing statements diagrammatically and creating magic circles. We will forgo an providing an introduction to existential graphs, A full introduction can be found in Don D. Robert’s overview paper, instead we will provide some examples to show what some formulae can look like when represented as beta existential graphs (Images are taken from John F. Sowa’s commentary of Peirce’s New Elements of Mathematics).

These are read as follows:

- A phoenix exists

- A phoenix does not exist

- Something exists which is both industrious and a boy

- An industrious thing exists and a boy exists

- Something exists which is not a phoenix

- Anything that thunders lightnings (depending on interpretation of the atomic predicates, this could also be read as “Anything that produces thunder produces lightning”)

- Something exists that thunders but does not lightning

- At least 3 things exist

- At most 3 things exist

- Exactly 3 things exist

Spells 8, 9, and 10 particularly showcase the ability of beta existential graphs as a prototype for magic circles due to their pleasing symmetry. It is important to note that any first order formulae with equality can be expressed in the beta existential graph system, meaning we can represent any compound, existential, or universal spells using beta existential graphs.

For Logicians:

- We say beta existential graphs can represent “any first order formulae”, but this is not entirely true as you do not have ability to mention objects in the domain by name using the unique symbol assigned to them, objects may exclusively referred to via the bound variables in quantifiers.

- Disjunction and conditional semantics come up again here, as beta existential graphs are essentially composed exclusively of conjunctions and negations, with the rest of the operators defined in terms of these. Material implication $A \rightarrow B$ in beta existential graphs is represented as $\lnot (A \land \lnot B)$, which do not have the same meaning in our proposed semantics. One solution to this is the multiple parse trees approach, and non-deterministically selecting if the graph $(A (B))$ represents $A \rightarrow B$ or $\lnot (A \land \lnot B)$, possibly depending on other factors such as the geometry of the circle.

Making Beta Existential Graph Magic Circles More Magical with Geometric Constraints and Modifiers Link to heading

Unfortunately beta existential graphs by themselves do not need to be very magical looking, take graphs 1-6 for example. We propose three solutions:

- First, we can start by applying the same trick we used for flat symbolic spells: applying symbolic substitutions to atoms so that each atomic predicate corresponds to a symbol, additionally we may overload predicate symbols based on how many arguments are passed to them similar to the overloaded operator symbols in APL(Note that the previous figure did not include any examples of beta existential graphs with binary predicates, see Sowa’s commentary for those).

- Second, we may place any number of geometric constraints on the spell. This includes things like reducing spell mana costs increasing fizzle chances or giving bonuses depending on how many lines of symmetry or nested levels exist in the graph.

- Third, we may wrap the entire graph in another circle to signify the sheet of assertion.

Desirable Properties of Beta Existential Graphs with Geometric Constraints for Spells Link to heading

The Beta Existential Graphs with Geometric Constraints system has a few very desireable properties which pull in different directions:

Geometric Constraints can encourage simple spells: Like how many first order logical formulae are logically equivalent, many beta existential graphs are logically equivalent: they cast the same spell using different circles. Occam’s razor like constraints may be placed by the world builder to encourage simpler spells where possible, by doing things like having the number of symbols (cuts, atoms, lines) in the spell factor into the total mana cost.

Geometric Constraints can encourage complex spells: Symmetry constraints can force mages to make spells more aesthetic, and include more symbols that add additional functionality than they may have otherwise to get bonuses or avoid penalties for this.

Ambiguity in conditional and disjunctive semantics can encourage unexpected behavior mitigation: Having multiple parse trees allows for spells who’s meanings are ambiguous and may do something unexpected if a different parse tree than the intended one is selected. Mages are encouraged to seek out spells that minimize ambiguity perhaps determined by other geometric constraints.

These constraints do not point towards a unified meta, but rather pull what spells should look like in different directions depending on situations spells should be used, how much mana a caster has, and how to prevent unintended consequences.